Testimonials

Catherine Lapoujade – Marie-France Coppeaux – Jean-Noël Delamarre – Pierre Hébert

Yves Charnay – Florence Miailhe – François Barbâtre – Jean-Jacques Lebel – Françoise Etchegaray

Catherine Lapoujade

It was a friend who had had Lapoujade as a drawing teacher at the ‘Ecole Alsacienne’ who introduced us. I had already decided to work in the cinema but at the time for a woman the opportunities were rather limited. Our meeting naturally led to a collaboration and I assisted him in the production and editing of some of his films.

Lapoujade was a painter, by taste, by vocation, by talent, of course, and also because it is easier, when you are 18 years old and live in the provinces, to draw and paint rather than to enter the world of cinema.

However, he had always been tempted by the cinema. At 10, he was making sorts of magic lanterns, somewhat whimsical projection devices, which he presented to his classmates. Despite this passion, he had to wait more than 25 years before acquiring the equipment he needed to realize his dream, owning a camera and a title bench and making his first animated films.

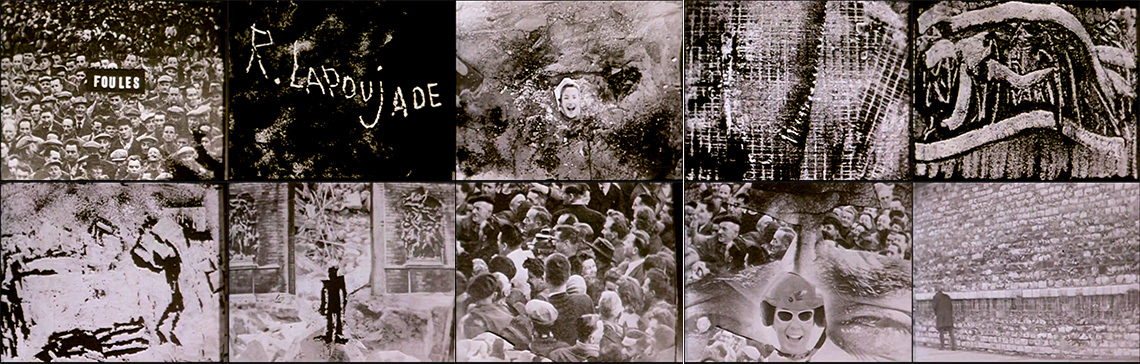

He was a craftsman who continued research on the materials used, the supports… In addition to the drawings, he used all the new techniques to which were added some ingredients from his personal recipe: salt, pepper, flour, sugar … and many other materials, paper, cut-out photos, iron filings, scraping of film… It is with these elements that Lapoujade has created an extraordinarily lively world like in his first film Foules (1960). This salt and this pepper, we do not recognize them, they lead us into a kind of prehistory. They have become a whole delirious universe.

He never gave up before having obtained the desired effect and did not hesitate to experiment with various avenues…In Three portraits of a bird that does not exist (1963), the drawings were scratched on the same surface, so it was necessary to each new image readjusting the scenery when the wings of the birds moved…and the extremely fast beating of the wings of the flying bird made the work enormously complex. We could shoot entire nights for a few seconds of film!

Rhythm, design and color were not dissociated, at least in the films he made at the time. It was a painting in perpetual motion… but a particular movement! It was not a question of imitating the real movement, but of showing it in another reality: the one he had in mind and this movement was completed by the sound element. His primary concern was to give the image, through sound, a dimension that it did not possess until then. He sought to avoid sound pleonasm at all costs.

On the other hand, he was not afraid to repeat a sound excessively. It was his way of arriving at delirium, a word which, for him, meant much more tragedy than unreason…

In Foules, every two or three minutes a girl laughs, a forced almost hysterical laugh. At first, the audience laughs too. Then this systematic repetition takes on such an agonizing character that, in the end, everyone recognizes this laughter for what it is: the most elementary cry of our condition.

Through his research in different fields, Lapoujade tried to create a cinema which he called “indirect” cinema, as opposed to direct cinema which encompassed the majority of films made at the time. It was for him: ‘to take sufficient distances from any subject to allow the multiple sensations of real life’. Thus his camera, while filming the essence of a scene, sometimes broke its unity by integrating parallel elements which would reinforce the impression of truth. This constant dispersion of tension corresponded to the multiple fleeting thoughts which, by accumulating “nothingnesses”, ended up constituting the reality of life. We perceived this vision in the Socrates. This film was not the culmination of his cinematic conceptions, but a platform for him to develop the experiments he had undertaken. A film that wanted to captivate the spectator by constantly surprising him and that would not mince the work. He was aware of the difficulties for some viewers to understand the film and a second screening was offered to access greater readability!

It is easy to imagine that his conceptions of cinema were not very easy to put into practice, but he always fought to go as far as possible in his projects.

This was the truth of Lapoujade: that of his painting and that of the cinema he was trying to achieve, in a constant back and forth from one art to another, which never ceased to enrich them both.

Catherine Lapoujade

Production Manager

July 17, 2023

Marie-France Coppeaux

I worked for more than two years on the animated film project “The Memoirs of Don Quixote”.

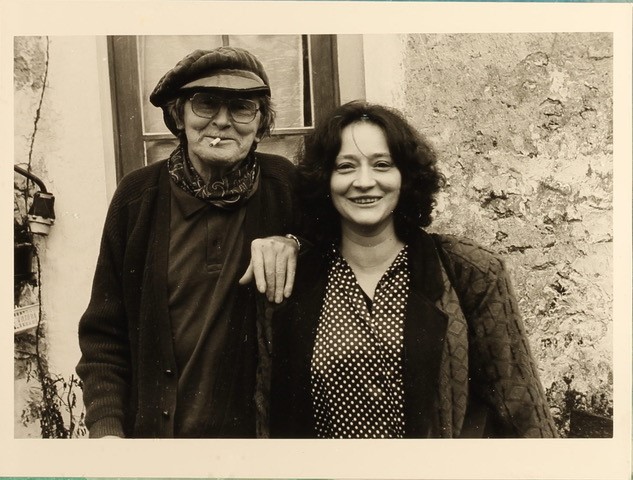

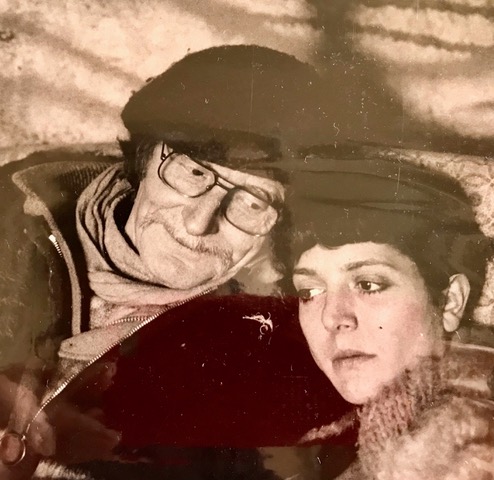

I met Robert Lapoujade in the spring of 1977. I was creating fabric objects, and he was looking for someone to make the costumes for the two puppets he had created for an animated film project.

So I worked with him on this extraordinary adventure, while sharing his life. The first months were tough because, without initial funding, the project had to be conducted in very austere conditions. This did not bother Robert. There was no longer any central heating in the house because he had dismantled his radiator pipes to make dolly rails… He contented himself with a fire in the fireplace in the main room. The house had become a gigantic workshop dedicated to the manufacture of puppets and decorative elements.

tournage du film 'Les Mémoires de Don Quichotte'

Passionate painter, curious about everything, sculptor, filmmaker, writer, he never stopped. He began his days in his painting studio, adding details to a painting in progress or preparing the next. Then he went to the barn which had been converted into a studio to work on the sets for the next sequence, after taking a tour of the welding workshop to finalize the details of the puppet structures. Then, he made some sketches, sudden ideas that he fixed on paper to memorize : an idea of a decoration or a painting project. He wrote the lyrics of the songs of his opera or refined the dialogues. Finally, he went to the sculpture workshop to work on making the mouths and foreheads that would give his puppets the full range of human expression.

In love with the absolute, he always tried to go beyond his limits, to go further in creation. For him, anything was possible with hard work, determination, passion: a brilliant autodidact, he loved challenges that forced him to go beyond the imaginable. He liked to quote this sentence: “appearing is a path to being” and had made it a guideline, a way to overcome moments of discouragement, to never let himself be defeated, and to continue to excel.

The feature film “The Memoirs of Don Quixote” could never be finished: it was a huge disappointment for him and a kind of defeat, because he said that this film would be the last he would make, his ultimate work. somehow…

Marie-France Coppeaux, designer of textile accessories

(December 2022)

Jean-Noël Delamarre

One of the most beautiful memories of my life is my first meeting with Robert Lapoujade at the Ecole Alsacienne, where I entered 5th grade in 1953-54.

Robert Lapoujade was the drawing and painting teacher, and his lessons were adventures in all areas: they could start with an invented story that captivated us, or with an approach to drawing punctuated by a tam-tam whose each strike deserved a line from us, fast or slow, or else to draw with your eyes closed after having observed a still life or a face for a long time… Quickly, won over, I took painting lessons at his house on Wednesdays with a few other students, which confirmed in my desire to be a painter.

Then one day, Robert Lapoujade procured a rostrum camera (“banc titre”) with a superb Eclair camera to film frame by frame. So while we were painting, he was working on his rostrum camera, which began to fascinate me as well. So much so that I quickly asked him if I could assist in his image work and gradually became an assistant: this will turn my life upside down. This is how I prepared for IDHEC (L’Institut des hautes études cinématographiques ), unfortunately without going there. So on his advice I entered the Higher School of Fine Arts to continue studying art and painting. But at the same time, I continued to assist him in some of his short films and later in his two feature films Le Socrate and Le Sourire Vertical.

One of my memories, among other things, of Le Socrate is of having painted a road over several hundred meters with blue paint powder! Which will not prevent me from traveling for miles to see the exhibitions of Robert Lapoujade, glorified by Sartre, Duras and many others. And then thanks to him, in 1965 I was able to obtain a rostrum camera for a professional need, while following the pictorial and cinematographic work of Robert Lapoujade, who had become for me like a second father and who, in the same way that my father, the sculptor Raymond Delamarre, guided me in my artistic life with great happiness. I paid homage to them both by asking Robert Lapoujade to write and speak the commentary on the documentary I made about my father, “L’Espace apprivoisé”, which he did with joy directly during a projection. Later I was able to make a documentary about him during a painting course “A Painting Lesson” that he gave and in which we hear and see his immense talent. I keep forever in my heart this great painter who gave me so much and whom I admired and loved.

Jean-Noël Delamarre, painter and filmmaker

(December 2022)

Pierre Hébert

I saw the film Prison by Robert Lapoujade in 1964. I was twenty years old, and I was developing an interest in animation. I was nourished by watching experimental films from the important collection of Guy L. Côté (one of the founders of the Cinémathèque québécoise). Prison, just like Foules (Crowds) left a very strong impression on me, comparable to that also left on me by the films of Norman McLaren, Len Lye, Robert Breer and Stan Brakhage. A personal pantheon was thus formed, of which Lapoujade was a part, an inaugural illumination whose influence would continue until today. This pantheon presided over my entry into cinema and defined the style of animation that would interest me forever.

Unlike the films of McLaren, Len Lye, Breer and Brakhage, Prison quickly became inaccessible. The Côté collection has dissipated and some important titles have been lost. In short, I was not able to see this film again before the summer of 2022, on the occasion of a conference devoted to Lapoujade. The strength of the initial impression had been maintained over the years, but the memory of the details had gradually faded. All that remained was the vague memory of the main theme: a prisoner scrutinizing the wall of his cell. Seeing this film again fifty years later was a real shock. I was suddenly confronted with the reality of the object which had become a sort of diffused myth.

I also had a vivid memory of a very radical animation style, where photography and animation, fixity and movement mingle, breaking up segments of live action, breaking down the movement frame by frame. It was also about a soundtrack often out of step with the flow of the image, in which are introduced, for example, long moments of fixity leaving the sounds in a paradoxical off-screen, at the limit of realism and phantasmagoria. The contours of this style appeared sharper to me than I remembered. Its radicalism seemed to me more voluntary and more assumed than what I remembered, making this film again, with even more force, an important and vital reference for my creation.

Pierre Hébert, filmmaker and multidisciplinary artist.

(December 2022)

Yves Charnay

When Robert Lapoujade came to Saint-Etienne to present his cinematographic works, all the students of the School of Fine Arts were present.

We immediately liked him a lot. His way of speaking, his humor, his simplicity, quickly conquered us. It goes without saying that what he showed us was astonishing. The graphic works of Robert Lapoujade revealed a world to us.

For my part, I was enthusiastic about his strange, non-existent bird, whose presence nevertheless fascinated us. It was “Portrait of a bird that does not exist”. When I spoke about this work to friends I did not want to use the term “animated film” because it seemed to me that it reduced the poetic dimension of the work. To describe this kind of animation I spoke of graphic film. I didn’t want them to imagine a traditional animated film. The world that Robert Lapoujade made us discover was far from that of Walt Disney. Of course “Portrait of a bird that does not exist” is an animated film but above all a dynamic pictorial work. The initial image was metamorphosed, delivering as it evolved interpretations constantly challenged in their succession. A somewhat infinite pictorial work. The dynamics of evolution brought a series of questions that opened up poetic worlds that transported us.

We had sometimes seen screenings of animated films from various countries whose narrative innovations had seduced us. But the art of Robert Lapoujade opened up a universe that enchanted us.

Robert’s personality impressed me a lot. This is one of the reasons why I went to Paris because I wanted to explore this world of animation. We met just before he entered ENSAD (L’École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs), where he taught for several years in the animation film department. We have become friends.

Yves Charnay, Artist

(December 2022)

Florence Miailhe

My mother, Mireille Glodek Miailhe, knew Robert Lapoujade well. They were both painters, and sypathetic to the French Communist Party. They appreciated each other and shared, especially at the end of their career, a conception of painting that was ultimately quite close.

They had been put in boxes probably too confining for them. Mireille in that of socialist realism and Lapoujade in abstraction.

They both found themselves teachers at the Decorative Arts in the 80s. Then thanks to a mutual friend,André Vidal who worked at Tallens, they gave painting lessons on the island of painters in La Ferté-Milon. It was around this time that my mother introduced him to me. We wanted, with a photographer friend, to make a book in screen printing of drawings that I had done in the hammam.

I greatly admired what I had been able to see of his films.

I had left the Decorative Arts where I had studied engraving, and animation was a dream that I did not feel able to achieve.

We met in Saincy. The whole house, the garden, the barn, were still filled with sets, objects and dolls from his Don Quixote. He showed us around his estate with a mixture of immense sadness and pride. He showed us the mouths of the characters who reproduced the phonemes to animate the lyrics of his opera.

He was immediately seduced by my drawings of the Hammam and asked me to write a text. He imagined himself, a blind masseur, feeling and caressing all these women within reach. He offered me a first text, very erotic, which I kept but which I did not use and another, wiser which is integrated into the book which we published.

As for animation, he gave me the best possible advice: buy a camera and go for it. I bought a 16mm camera, I never used it but it freed me up and when I showed him the cut of my first film, Hammam, he introduced me to Jean-Noël Delamarre to work on his rostrum camera and to Natalie Perrey for editing. It is largely thanks to them that I was able to do animation, my job and my passion.

I had the impression of discovering a new family accompanied by the benevolence and encouragement of Lapoujade. I can still hear his voice, a little scratchy, which always kept a touch of accent and cheerfulness, despite all the difficulties he was going through.

One day we were invited to discover the first 20 minutes of Don Quixote. In the middle of the film we saw a black dot growing on the images. The film was burning. All the worried spectators turned to Lapoujade, he was smiling. I probably didn’t know him well enough, but I had the feeling that nothing ever seemed to shake his optimism and good humor.

He came to spend some time at my parents’ house in the south. In the morning you could hear his bones cracking. he said laughingly that little by little he was rusting, like Don Quixote and all his puppets at Saincy who could no longer move.

I am happy that he was able to see my first film which owes him a lot.

Florence Miailhe, director

(December 2022)

François Barbâtre

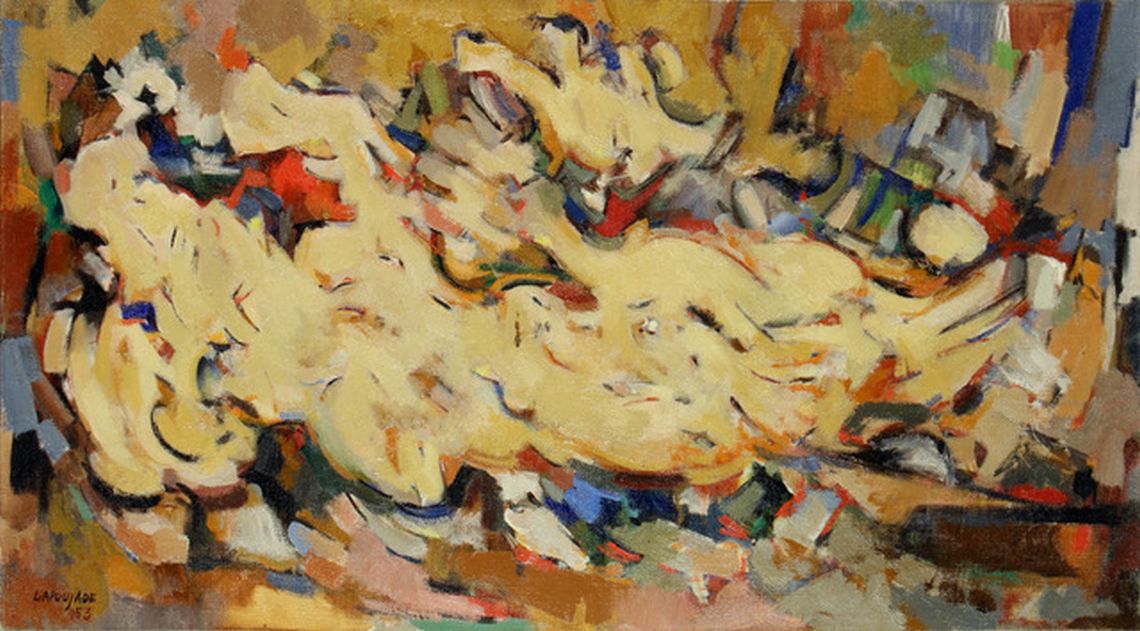

I discovered Lapoujade at the Salon de Mai in 1958, presented by his dealer Pierre Loeb. Lapoujade exhibited ‘Baigneuse au bord de la mer’ which I had my father buy.

I remember the arrival of this painting in Laval and the unpacking in front of an assembly of businessmen with whom my father worked, their astonishment but also the enthusiasm of my father!

The day after this purchase, I went to see him on rue Beautreillis where he worked in a large room, in an old dilapidated hotel (in the courtyard there were shared toilets, a shoemaker!).

He received many friends there. From that day on, we were very close.

In his fury to be ‘at the heart of the matter’, there was only room for painting and nothing else.

He was a warm man and for the young painter that I was, I was very fortunate to be able to go see him at any time.

It was a difficult time since the painting swung between an evocation of the subject – without ever falling into a realistic representation, considered unseemly at the time – and abstraction.

It was necessary to suggest, while being as close as possible to an emotion that was always new as soon as the model was revealed (the models were not professionals, never; I even introduced him to one of my young cousins, in red stockings!) .

Knowing him better, he was shy and blushed easily! Even when he had no money, he only traveled by taxi…

The confidence and intelligence of J. L. Ferrier* counted for a lot. He often gave very rowdy lectures because ‘Abstraction’ dominated at that time. However, the recognition of Balthus by the general public and of Alberto Giacometti (defended by Sartre, just as he had supported Lapoujade) changed the situation.

Subsequently, my father bought a whole exhibition from him. He was then able to get a camera and it was the beginning of the cinema. But before, I remember the endless sessions, where, among other things, he photographed the rotting of an apple day after day. A key moment when “time” made its appearance.

The cinema part that fascinated him is another story in which I also participated as an extra…

To return to painting, he did not like Cézanne! And the Chinese painting that became my business was to distance us without our ever losing sight of eachother. I showed him the reproductions of Cézanne’s drawings, the ruptures of the drawings, a dimension of emptiness -the word is out- seriously bothered me but for him it couldn’t be his business… to grasp his subject until it smothered it, he had to ‘stuff’ it, that was his word…

Unfortunately, I don’t have time to take this text written all at once and send it to you as it is… by reviewing the paintings there would still be a lot to tell…

One thing remains, this passion to incarnate, that painting gives body to the letter…

A vanished world?

Francois Barbatre

(December 2022)

*J.L.Ferrier (1926-20022), Art historian and teacher at ENSAD

Jean-Jacques Lebel

Robert Lapoujade was one of the rare artists of the immediate post-war period (to whom lazy critics and uneducated auctioneers stuck the derisory label “School of Paris”) who knew how to free himself from the trap which consisted in believing that the field of visual art can be split in two: on one side “the figurative” and on the other the “abstract” or the “concrete”. Such was the blind spot or, more exactly, the blind system on which the commodity ideology was already operating at that time.

If Lapoujade was one of those who succeeded in freeing himself from this trap, it is probably thanks to his frequentation of thinkers who were foreign (or supposed to be such) to the artistic thing : starting with Sartre, who prefaced one of his exhibitions, to Merleau -Ponty, author of a “Phenomenology of Perception” and, later, to Kostas Axelos, translator and exegete of Heraclitus, Nietzsche and Marx, director of the excellent review Arguments and of the collection of philosophical works of the same name . Arguments was also the place, located in the attic of Éditions de Minuit, rue Bernard Palissy, of a permanent and disruptive intellectual and political debate open to contributors and readers alike. It was during one of these editorial meetings, with Axelos, Morin, Duvignaud and Nora Mitrani that Lapoujade and I met. It was a question of preparing the issue of the magazine entirely devoted to art, on which Lapoujade collaborated. Another day, a young professor of philosophy arrived from Lyon, already very intense, by the name of Gilles Deleuze. This meetingwill modify (after May 68) the course of my existence. Lapoujade was therefore arguing with Sartre or with the post-Marxists of Arguments on an equal footing, having acquired the status – much envied, by me anyway – of artist-thinker, in contrast to the robotic functionaries enslaved to the market or to public opinion.

For my part, I was only a beginner, barely an “apprentice”, whom Axelos had generously undertaken to introduce to Heraclitus, Nietzsche and Marx. It was with ears and eyes wide open that I attended a session of unlimited bodily expression in Lapoujade’s studio: he had assembled a dozen students, mostly young women, to whom he taught the art of the physical and mental “acting out”, to the sound of recordings of thundering African tam-tams. It is the insane choreography of these unleashed bodies that Lapoujade filmed in black and white in “Foules”.

This experimental work immediately propelled itself into the heart of the nascent movement of self-managed, self-produced and self-disseminated Underground Cinema that Jonas Mekas and his New York friends (Brakhage, Mead, Warhol, etc.) were organizing across the Atlantic at the same time as within the Film Makers Coop.

It is thanks to this film, shot in 16mm or 8mm if my memory serves me correctly, that Lapoujade succeeded in freeing himself from the trap and the false problem already mentioned, from the inanity of the artificial opposition between figuration and abstraction. , and, in doing so, managed to implement its own aesthetic process. We (Alain Jouffroy and I,) invited Lapoujade to project his film within the framework of the great international demonstration Anti-Procès 3 in Milan, in 1961. A lively debate ensued. The upsurge, as a disturbing element and an incitement to the generalized decompartmentalization of all political and artistic activities — later Deleuze and Guattari would forge the concept of Chaosmosis in this regard — characterized the period of gestation and preparation for May 68 around the world, including in Paris, where, in 1960, a real counter-cultural bomb exploded: The Manifesto of 121 for the right to insubordination in the Algerian War, which succeeded in uniting not only militants of various currents of the extreme left but also the living forces of literature, philosophy, visual arts, cinema, scientific research, music around a collective anti-state, anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist action: a call for desertion. Lapoujade and I, like so many others, countersigned it. It came from Maurice Blanchot and was co-drafted by Dionys Mascolo and Jean Schuster before being endorsed by several hundred people, some of whom met within the Action Committee of Revolutionary Intellectuals.

Today, in 2022, the regressive slump is so deep that it is difficult to recognize that such a committee could have existed and exerted a real influence on political life. But that was unquestionably the case. Such was the existential context in which Lapoujade inscribed his pictorial and cinematographic activities, both centered on the problematic of image-movement. The reference to Deleuze is all the more deliberate because there is an indisputable link between the philosopher and the painter: it was Lapoujade who forged the concept of showing, which Deleuze would develop to the point of making it autonomous, specific, which will completely transform the practice of the exhibition specific not only to artists but to Duchampian viewers, their indispensable cooperators. From now on, the art of showing and the art of editing (in the cinematic sense of the term) will be one. This is why it would be appropriate, it seems to me, to observe Robert Lapoujade’s painting through the optical system or rather the mental device that he developed and used to make “Crowds” and his paintings of the same period. . He painted, literally with his camera, and he automatically filmed as one draws.

I don’t know if Deleuze saw “Crowds” or not. We can doubt it insofar as he almost completely excluded experimental cinema (and the Underground Cinema) from his fundamental theoretical works, published in two volumes: the Image-Movement and the Image Time, which did not in any way prevente him from pointing out his decisive borrowing from Lapoujade of the concept of showing… I also don’t know the reasons why he didn’t want to see the films of Mekas, Mead, or Brakhage without even mentioning the marvels of Ricci Lucchi and Gianikian… Questioned several times by me, he did not answer me. One day when we were discussing extraordinary cinema, in one of his seminars at the University of Vincennes, I told him of my unreserved admiration for Jean Genet’s film, Un chant d’amour, definitely out of the mainstream by the express political will of the author, Deleuze told me that he had never seen it – I was flabbergasted – and yet he took into account what I told him about it. On the other hand, Lapoujade’s painting was very probably known to him, at least one can assume so. All I know is that they sympathized during a few Arguments meetings and that is enough to encourage us to take an if not “Deleuzian” look, it would be abusive, at least rhizomic on this painting. I will cite two good examples:

1. La Vénus florentine (1953) methodical destruction of the Venus of Urbino by Titian, preserved in the Uffizi, where the naked goddess in question literally blends into the landscape even if it means almost disappearing there like a piece of sugar in a glass of water. Art comes from art, of course, but by what means?

2. The Triptyque contre la Torture (1961), deposited at the IMEC, which explicitly refers to a traumatic event that occurred in reality, that of the generalization of torture practiced industrially by the French soldiers during the occupation and the war of independence of Algeria and, particularly, the serious abuse, rape and torture with electricity (with electrodes placed on the breasts, sex and legs) inflicted on Djamila Boupacha, the FLN militant of twenty -three years old, who had the extraordinary courage to lodge a complaint and to name her executioners in Algiers, in 1960. Drawn sketches of the Triptych against Torture appeared, at the same time as a portrait of Djamila drawn by Picasso and a large canvas titled Djamila painted by Matta, in the book by Gisèle Halimi and Simone de Beauvoir published by Gallimard in 1962, whose title was precisely Djamila Boupacha. This irrefutable historical document is a definitive indictment of the inherently criminal, and often sexually criminal, nature of colonialism. Here, ethics take precedence over aesthetics.

Challenging Socialist Realism, the trickery touted by Aragon and other Stalinist propagandists, but also geometric abstraction, the pictorialism adopted by Lapoujade used techniques that could be described as cinematographic: blurring, reframing, change of focal length, freeze frame. This production process resulted in the abolition of the classical perspective in place since the Renaissance. Visibility is thus reduced to a single plane, thus deprived of a background, as in the Trecento painting dating from before the invention of perspective. It is not that the content is absent from this painting, on the contrary, it is there, before our eyes, being the subject of a specific display but in the state of a blurred movement-image, like a “fixed explosion” hallucination whose real consistency requires to be thought and constantly rethought with each furtive or insistent glance launched by each viewer and each viewer. As for the perception occasioned by the display, no consensus is guaranteed. Only one certainty persists: painting exists only through and in the work of the gaze.

Leonardo warned: È cosa mental!

Jean Jacques Lebel

(December 2022)

LES MÉCANISMES DE LA CRÉATION

Saincy. Matin d’été. Vol ivre des papillons bruns et or. Fourmis à toutes pattes sur des parcours compliqués. Agitation ailée des guêpes. Brisures froissées du feuillage. Gribouillages sonores.

Tandis qu’alentour tout vibre et tout bruit, Robert Lapoujade, assis sur la terrasse, contemple immobile le mur de la maison. Quand il parle, c’est pour dire les signes multiples gravés par le hasard dans la pierre et le ciment.

Il dit les casques étincelants des cohortes romaines, les lances imaginaires, les têtes des chevaux aux yeux fous, et sous sa main qui effleure le mur comme un pinceau, naissent d’innombrables combats, se démultiplient des pattes, se dessinent des becs d’aigles, des étendards, de grands taureaux dressés, des couples emmêlés.

Sous la poésie de la peinture. Et bientôt, là-haut dans l’atelier, entre les signes lus sur le mur et les couleurs de sa palette, va naître une toile, une « Grande Bataille », où comme sur le mur, cavaliers, chevaux, heaumes et boucliers s’enchevêtreront et se heurteront en joutes sauvages.

Plus loin, les craquelures du ciment prennent des visages et des corps d’hommes torturés, des mouvances blessées de champs d’oliviers ou les formes ployées de danseuses classiques. La main pinceau s’adoucit alors pour suivre dans une tâche de mousse la courbe d’une femme allongée. Elle devient caresse pour suivre le contour d’un sein, l’ombre plus marquée d’un sexe. Vingt ans plus tôt, la même caresse filmée avait exalté la somptueuse beauté de Cécile dans « Enquête sur un corps ».

Sensualité, Érotisme, Sourire vertical. Autant de tableaux, de films, qui représentent la femme recréée sans cesse au fil de son désir. Solaires. Éclatantes dans leur nudité, « Les Trois Femmes » qui se déshabillent dans les oliviers en témoignent dans l’atelier.

Peut-être aussi, puisque l’essence même de la création pour lui est le cri, la femme s’inscrit-elle dans cette symbolique.

Crier et créer, deux mots qu’il veut synonymes.

Deux mots dont il poursuit l’explication sur les murs de Saincy, où défilent pêle-mêle des pharaons incestes, des conques marines, des pylônes, des bacchanales hallucinées et des rondes de chevaux montés par des amazones nues.

Dérives. Associations d’idées. Il évoque Faulkner et Joyce « et les hauts espars aux voiles troussées sur leur traversins de hunes », Malcolm Lowry, et la lave de couler des volcans et les tempêtes de déferler sur les rochers de granit… Il est arrivé à la porte de la maison ! Imaginaire. Fol imaginaire de Lapoujade, où se mêlent les souvenirs de lectures et les souvenirs vécus, les corps de femmes aimées, les voyages lumineux en Grèce et à Venise, les conversations avec Sartre, Mai 68, l’inculpation lors du procès des 121, la grotte où il vécut seul pendant six mois à dix-huit ans et où il peignit inlassablement des œufs avec des feuilles écrasées et des coquilles d’escargots…

Réel. Réalité. Transposition du réel. Clés pour la mise en scène. Clés pour des images et des histoires. Celle du poirier magique immense, de l’autre côté du jardin, au pied duquel sort un trésor caché par le Templiers. Celle du cerisier magique qui, au printemps, se couvre d’un côté de fleurs blanches et de l’autre de fleurs roses, parce qu’il sait – paraît-il – qu’il pousse dans le jardin d’un peintre.

Des images aussi pour Don Quichotte, Sancho, Cervantès et Dulcinée. Mais des images arrêtées… Et Don Quichotte auprès de ses 40 Bouches plisse un de ses nombreux fronts et caresse dubitatif sa barbe qui s’étiole.

Les moulins contre lesquels il faut se batte sont parfois de redoutables géants.

En attendant, Lapoujade déclare qu’il faut « sucrer » les loirs de la grange et enlever les toiles d’araignées. Et Sancho de chanter le refrain appris dans la tour :

« L’homme n’en finit pas de vivre

L’homme n’en finit pas d’aimer. »

Françoise Etchegaray, 1981

Cinéaste et Productrice